The Vanishing Language of the Guna Yala Islands

Six Months in the Americas, Part 25

Off the coast of Panamá, lies a group of more than 300 islands. Guna Yala (once known as San Blas) is a self-governing territory called a comarca, which covers a strip of land in northeast Panamá as well as the archipelago of 365 islands.

The people who live there kicked outside forces from their lands decades ago and now control the area separately from Panamá. Traditionally, the Guna are a matriarchal society, and they also recognize a third gender called Omeggid.

I’d dreamed of visiting Guna Yala ever since I interviewed my friend Asia about leading tours for high school groups in the region. The archipelago seemed a space far removed from the mainland, where people moved about by boat, and the beaches were pristine and unspoiled.

To get to Guna Yala, you must hire local companies to take you in sturdy Toyotas through the dense jungle to the Caribbean Sea. This journey takes about three hours from Panamá City. You’ll go through a passport check as you essentially enter another country. There, you’ll board a small, seafaring boat and head out to one of the archipelago’s 365 islands, 50 of which are inhabited.

You may sleep in a small cabana which usually includes a comfy cot with bedding, a fan to cool things down, and electrical plugs to charge your electronics. This area of the islands is geared toward tourists and has a secluded, party atmosphere.

I was lucky enough to also visit the part of the islands where people live and work, thanks to Asia putting me in contact with cultural ambassador Gilbert Alemancia. Gilbert spoke to his family and offered me a boat ride to meet them and learn more about their language, Dulegaya, which translates more literally to “people mouth.”

I'm especially interested in languages at risk of extinction, having studied linguistics in grad school and written my thesis on the revitalization efforts of endangered languages in northern Spain.

When a language vanishes, a wealth of knowledge dies with it. Not only is the last native speaker gone, but an entire group’s cultural wisdom about their region, beliefs, practices, and past. Scholars cannot get back these resources, and even with revitalization movements, endangered languages walk a fine line between being preserved and perishing.

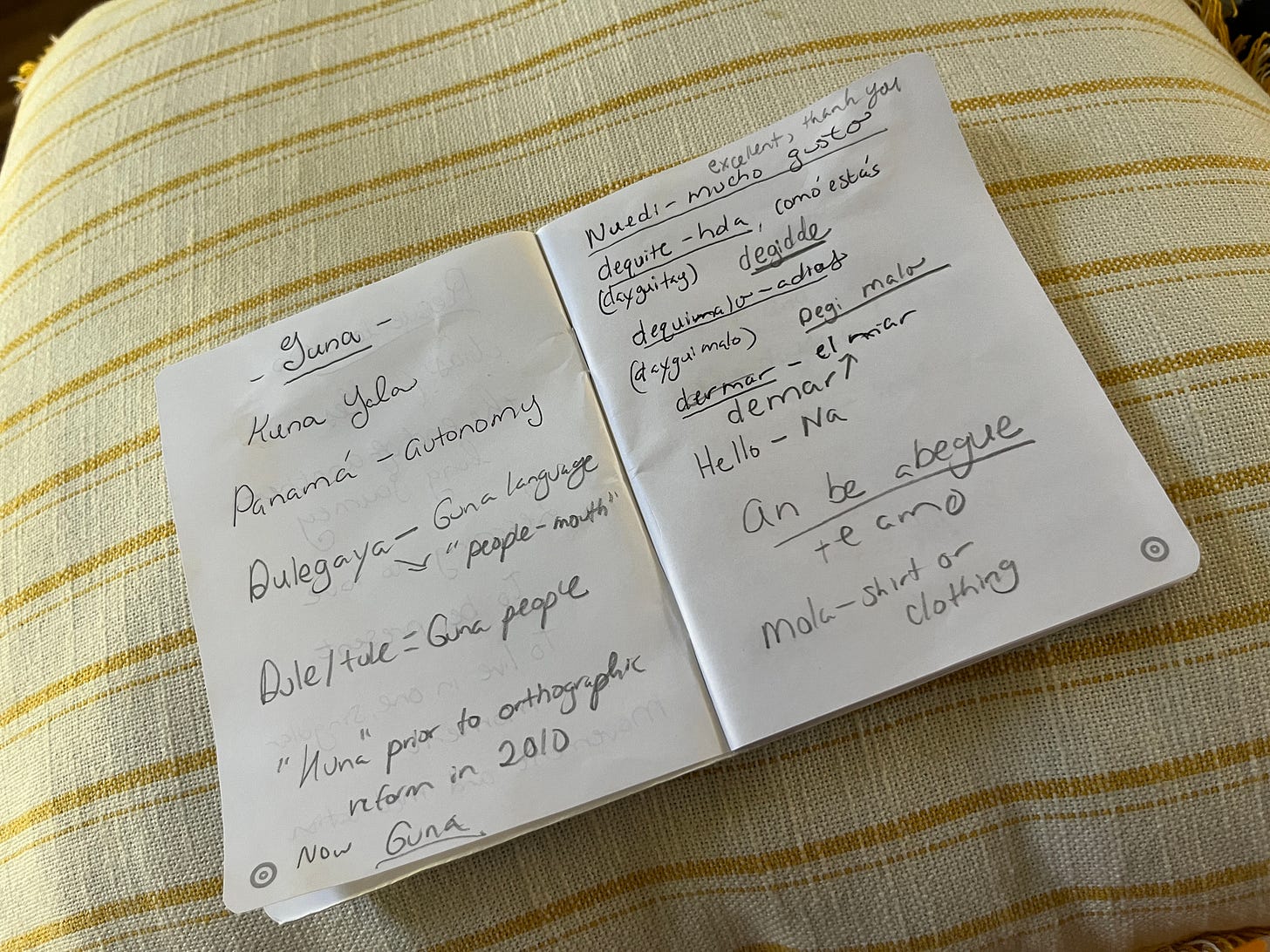

Gilbert’s family were kind enough to answer my questions and share a few words of Dulegaya which I copied in my notebook. They also showed me the beautiful handmade mola they made, and I bought a headband from Gilbert’s mother.

The Guna do an extraordinary job of preserving the natural beauty of the islands. The beaches are well-cared for; homes are clean and tidy. However, you still see the effects of tourism on the archipelago.

For example, we got to take the boat to a massive sandbar floating in the ocean. There, as we walked along the sand, we could see giant starfish right beside our toes. We saw maybe two starfish that day and were cautioned not to touch them or get too close. Our guide shared that there used to be hundreds of starfish in this area, but human interference hurt them, and now there are only a few.

However, thanks to efforts from cultural ambassadors like Gilbert, conservation is underway as the Guna work to preserve not only the beauty of the islands, but their language and way of life.

As I learned when studying linguistics, more than a language is lost when it is no longer spoken. The wider world loses the knowledge, cultural wisdom, and dignity that comes with its speakers.

I’m grateful to Gilbert and his family for their insights into the islands and their efforts to preserve their language and culture. You can reach out to Gilbert or follow him online to learn more about the tourism and traditions of Guna Yala.

Thats new to me! I once stumbled upon a self-governed territory in the mountains of south Mexico. Didn’t know about Guna Yala, thank you!

Our oceans are so fragile. An important post Ashleigh as a reminder to us all.